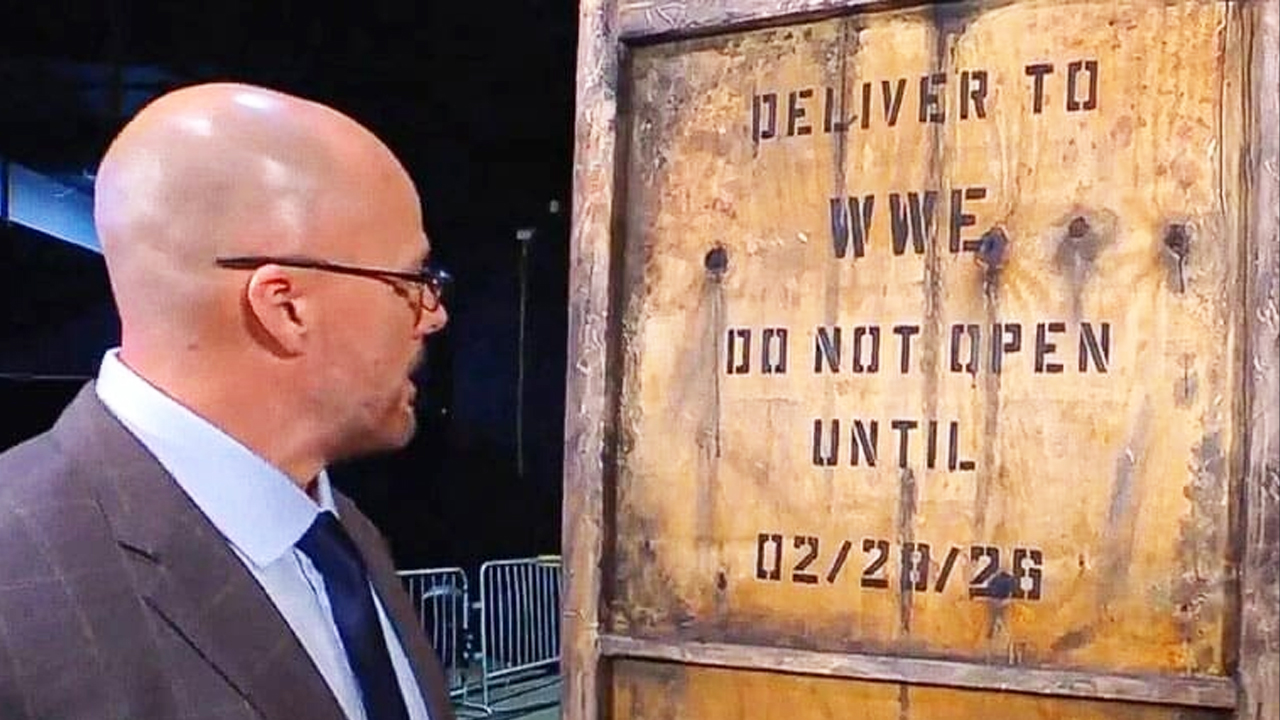

2026-02-26

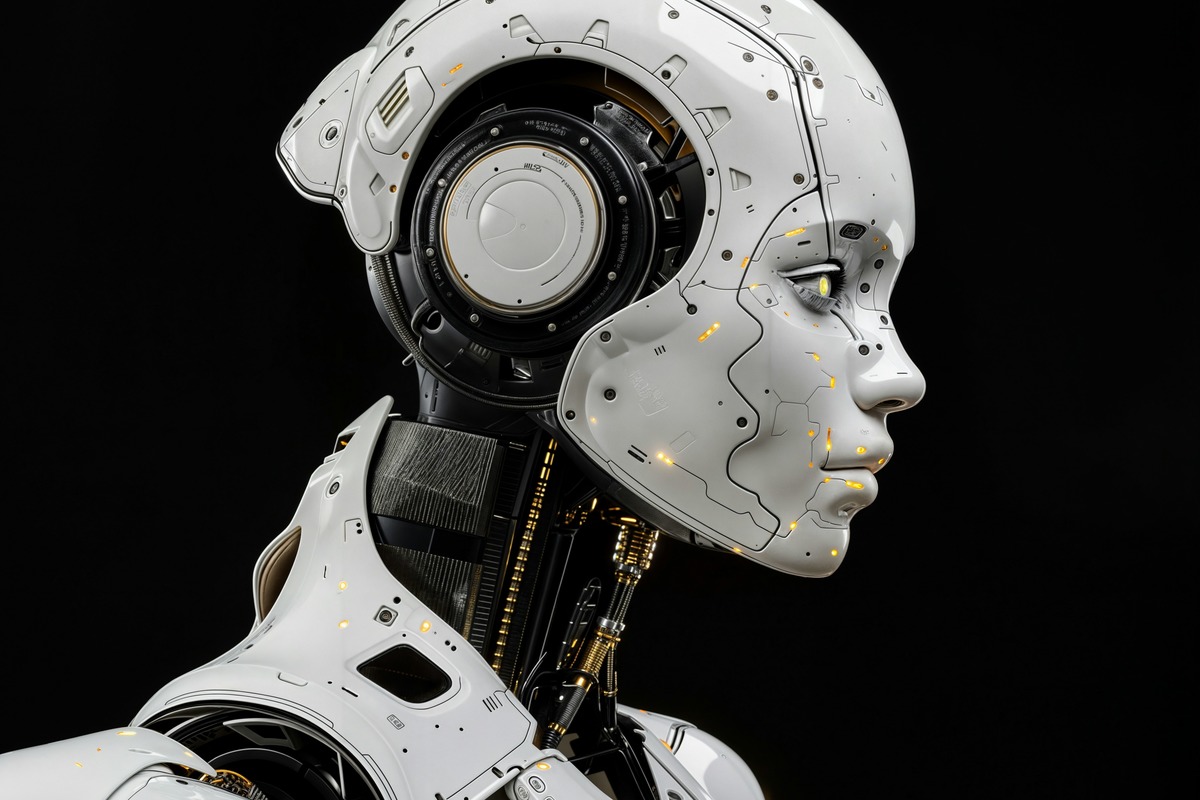

ServiceNow resolves 90% of its own IT requests autonomously. Now it wants to do the same for any enterprise

ServiceNow is handling 90% of its own employee IT requests autonomously, resolving cases 99% faster than human agents. On Thursday it announced the product technology it wants to use to do the same for everyone else.Organizations have spent three years running pilots that stall when AI gets to the execution layer. The agent can identify the problem and recommend a fix, then hand it back to a human because it lacks the permissions to finish the job or because no one trusts it to act autonomously inside a governed environment. The gap most teams are hitting isn't capability. It's governance and workflow continuity.ServiceNow's answer is a new framework called Autonomous Workforce; a new employee-facing product called EmployeeWorks built on its December acquisition of Moveworks; and an underlying architectural approach it calls "role automation."From ticketing system to AI workforceServiceNow has been building toward this for two decades. The platform started as a ticketing system, evolved into a workflow automation engine, and spent the last two years layering AI onto that foundation through its Now Assist product. What's different is that the new approach stops treating AI as a feature sitting on top of workflows and starts treating it as a worker operating inside them. That shift, from AI that assists to AI that executes, is where the broader enterprise market is headed. ServiceNow is making a specific architectural bet about how to get there.The announcement has three parts: ServiceNow EmployeeWorks lets employees describe a problem in plain language and have it fixed without filing a ticket; Autonomous Workforce executes work end to end; and role automation is the architectural layer that governs how those specialists operate inside existing enterprise permissions.Most enterprise AI assistants including Microsoft Copilot and Google Gemini require employees to know which tool handles which problem. Moveworks, which had 5.5 million enterprise users before the December acquisition, was built around a single entry point that routes across that ambiguity automatically.Bhavin Shah, founder of Moveworks and now SVP at ServiceNow following the acquisition, framed the problem directly in a briefing with press and analysts. "Over the last two years, organizations have raced to adopt AI, but in many cases that rush has created fragmented tools, disconnected AI experiences and employees bouncing between systems just to get simple things done," he said.Why role automation is different from a regular agentServiceNow is proposing a new architectural layer it calls role automation, and it differs from the agents most enterprises are already running.Conventional AI agents are task-oriented: they're given a goal, they reason toward it and in doing so they figure out what they're allowed to do at runtime. That creates problems in enterprise environments where governance, audit trails and permission boundaries aren't optional.With role automation, an AI specialist does not reason its way into permissions. It inherits them. The same access control framework, CMDB(configuration management database) context, SLA (service level agreement) logic and entitlement rules that govern human workers on the ServiceNow platform govern the AI specialist from the moment it is deployed. It cannot exceed its defined scope. It cannot self-escalate privileges based on what it learns mid-task.The company draws a three-tier distinction: task agents handle individual automation steps, agentic workflows mix deterministic and probabilistic execution, and role automation sits above both as a fully virtualized employee role with defined responsibilities and pre-inherited governance.The first product built on this architecture, the Level 1 Service Desk AI Specialist, handles common IT requests end to end — password resets, software access provisioning and network troubleshooting — documenting each resolution and escalating to a human agent only when it hits something outside its defined scope.'Don't chase butterflies'Alan Rosa has seen what happens when AI governance fails in healthcare. As CISO and SVP of infrastructure and operations at CVS Health, he manages AI deployment across 300,000 employees where compliance isn't optional. Speaking at the same briefing, his framework for scaling AI maps directly onto what ServiceNow is claiming architecturally. CVS Health was already a customer of both ServiceNow and Moveworks before the December acquisition. Rosa said the combination of the two platforms is encouraging and that the potential is "coming to life," though CVS Health has not committed publicly to deploying Autonomous Workforce."Boring is beautiful," Rosa said. "Predictable. Stable. You have to start with responsible, explainable AI. No bias, no hallucinations, clear guardrails. Everyone understands the rules." On the temptation to chase the newest AI capabilities before governance is in place, he was direct: "Don't chase butterflies. Focus on gritty, unsexy, operational use cases. The ones with real ROI that have an impact on people's lives."Rosa's approach treats AI as a continuously evolving set of capabilities requiring dynamic rather than static testing. CVS Health runs every AI use case through clinical, legal, privacy and security review before it touches production. "Static review doesn't cut it when AI is learning and adapting," he said. "Wash, rinse, repeat."Rosa's framework requires governance to be embedded in the deployment architecture from the start, not retrofitted after a problem surfaces. That is precisely the claim ServiceNow is making about role automation. AI specialists that inherit existing enterprise permissions and workflow logic are structurally less likely to break governance boundaries than agents that determine their own scope at runtime.What this means for enterprisesFor any organization evaluating agentic AI, regardless of vendor, the practical question is simple: Does your AI governance live inside your execution layer, or is it sitting on top of it as a policy document that agents can reason past?That is what ServiceNow is trying to solve with Autonomous Workforce and EmployeeWorks, baking governance and workflow context directly into the agentic layer rather than bolting it on afterward. For practitioners, the starting point is governance architecture, not capability. Before deploying any agentic AI, map where your permissions, workflow logic and audit requirements actually live. If that foundation isn't in place, no agent framework will hold at enterprise scale."Scale and trust go together," Rosa said. "If you lose trust, you lose the right to scale."

.jpg)

.jpg)

(55).jpg)